I had been trekking for several days in the otherworldly heights of the Himalayas. The temples were smaller versions of Lhasa’s Potala Palace; the architecture and art just one of the traditions the Tibetan people took with them when they fled Chinese expansion.

Tibetan Buddhism — and the sophisticated art that is deeply intertwined with the religion — has earlier roots on the Tibetan plateau. 15th century disciples were dispatched to the far corners of the region, including these temples in Ladakh. I visited a dozen monasteries, maybe more, in increasingly remote locations. Once, we entered a site on the top of a solitary hill and the building seemed to have been abandoned, though three carved masks hung from a support post in the middle of the bare room. In another, the dim light leaking in from the eaves revealed walls covered with hundreds of manifestations of the Buddha. And one held a golden statue with seemingly thousands of hands, each one holding a unique object.

It was overwhelming. It was not just the journey – though that was taxing indeed. It was the rich maroons and oranges, the gold leafing, the tiny details, the smoky light from the lamps, the quiet of the monks in their saffron robes. The art was — still is — inseparable from the experience of viewing it. But I did not understand what I was seeing. Why were there so many of these little Buddhas? What was I supposed to learn from their serene eyes, their elegantly posed hands? Why were those figures so fierce and angry? What was with all the skulls?

Here are a few themes that you’ll see repeated over and over in Tibetan Buddhist art. And take note — this is just an introductory look at the complex iconography represented in this deeply symbolic tradition; there’s a vast well of knowledge to tap in to, consider this just a starting point. It’s also worth noting that unlike much European religious art, Tibetan religious artists were, historically, anonymous, working from specific guidelines to create representations of beings both historical and figurative. There are new Tibetan artists who reference the ancient traditions, remixing them to create modern visual expressions with roots in a complicated, politically divided nation.

So many Buddhas

Those temple walls covered floor to ceiling in Buddhas the size of my hand weren’t all Buddhas. The work could have also been of historical figures, mythical deities or bodhisattvas — enlightened beings who help others achieve spiritual awakening. A bodhisattva is on the way to becoming a Buddha, but has committed to delaying his own enlightenment until all other beings have become enlightened.

With so many hands

Those well versed in Tibetan art can use the number of hands, the position of the hands and the objects in those hands to identify who the painting or sculpture represents.

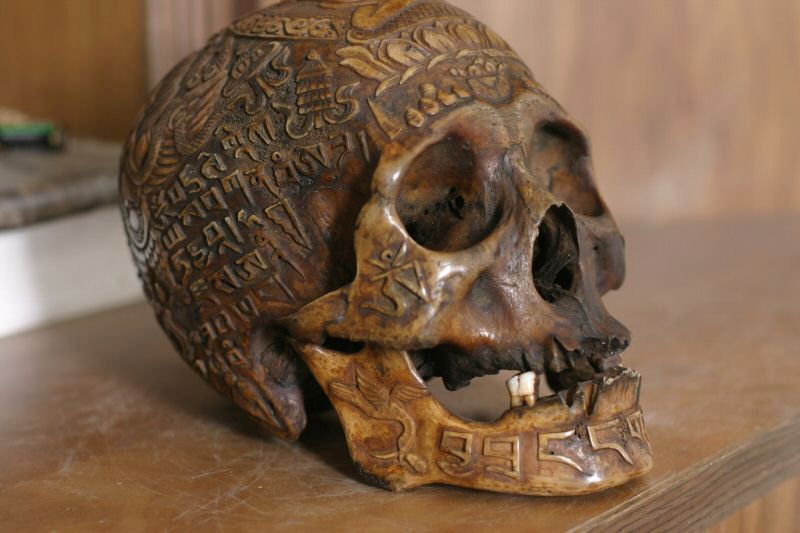

And those morbid skulls

Skull bowls, and skull crows and skeletons, and red beings with fangs — death is never far from the surface of Tibetan Buddhist art. These images don’t just reference the impermanence of the flesh, they can also represent vanquishing desires and shortcomings. Those fierce-looking demons aren’t so much about fear as about redirecting negative energy to overcome human faults.

Five colours

Colour has its own symbolism and there are five dominant colours in Buddhist art — black, white, yellow, red and green. Each colour is associated with a particular Buddha, but it’s also associated with a transformation — blue represents anger transformed into calm wisdom, for example. And each colour is associated with a body part. Colour is just one more factor that helps you identify who you’re looking at when you view Tibetan Buddhist art — its selection is highly intentional.

And what about those sand paintings?

This painstaking artwork is undertaken by a group of monks who work together for days — sometimes weeks — to create a meticulous mandala. The mandala is typically a symmetrical representation of the universe; a series of concentric squares with a circle in the middle. It’s a tool for meditation, and when it comes to the creation of a sand mandala, the work of making one is a meditation unto itself. Upon completion, this intricate work is destroyed, the sand swept into the middle, and then poured into a body of water. This act of creation and destruction is a poetic reminder to avoid attachment and to remember that nothing — nothing — is permanent.

![10 best airports in Asia in 2016 [RANKED] kuala-lumpur-international-airport-best airports in asia in 2016 by skytrax ratings](https://livingnomads.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/29/kuala-lumpur-international-airport-best-airports-in-asia-in-2016-by-skytrax-ratings-218x150.jpg)